Once upon a time, hip hop was seen through the lens of a hip hop magazine. Join Gazankulu.com as Bushbuckridge hip hop artist Ribelatti Feragummi pours a little liquor to the fallen pages

By Ribelatti Feragummi

In a time before hyperlinks, likes, and viral tweets, there existed a world where fans would walk into a bookshop, handpick a glossy hip hop magazine, and exchange their hard-earned cash for a piece of the culture. Some of us had to wait for one of the advanced ninjas to receive his subscription from overseas. Those crisp pages were more than just paper—they were portals to another world. They were the voice of a generation that didn’t just listen to the beat; they lived the words, embodied the style, and carried the culture. For the hip hop die-hard, no single magazine left the room once it was purchased unless it was borrowed and never returned, a sacrilege in the tight-knit community. These publications piled up like trophies, preserved with the kind of care usually reserved for first-edition novels, each representing a chapter of hip hop history now fading into oblivion.

R.I.P – The Source (1988–2014)

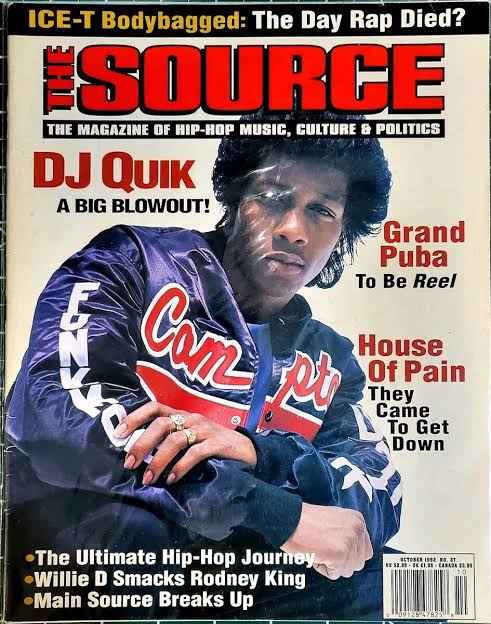

In the late ’80s, when hip hop was finding its voice, The Source was born. Often referred to as “The Bible of Hip Hop,” this magazine captured the essence of a culture that had only just begun to scratch the surface of its global influence. Founded in 1988 by Harvard students David Mays and Jon Shecter, The Source became the first national magazine to be dedicated exclusively to hip hop music, culture, and politics.

Under the editorial vision of Reginald Dennis, who joined in the early ’90s, the magazine reached its golden era, becoming a tastemaker. The famous “five-mic” rating system in The Source was gospel, determining an artist’s credibility. Nas’s Illmatic earned five mics, cementing both his and the magazine’s authority in the game. The writing talent on display included contributors like Kim Osorio, the first female editor-in-chief, and music journalist Elliott Wilson. Together, they curated a magazine that went beyond music, offering political commentary, fashion spreads, and deep dives into hip hop’s unsung heroes.

Artists like Tupac, Biggie, Jay-Z, and later, Eminem graced its covers. It wasn’t just about the hits; it was about the cultural edge these artists possessed. The Source was less interested in who was hot and more concerned with who was real—it captured the soul of the streets.

Sadly, as hip hop shifted from vinyl to digital, so too did The Source. It lost its grip on the culture, battling financial struggles, internal conflicts, and a rapidly changing media landscape. By 2014, the print magazine had bled out, a relic of a time when hip hop’s pulse was tangible on every page.

R.I.P – Vibe (1993–2014): When Music Met Fashion

Founded by legendary music producer Quincy Jones in 1993, Vibe was where hip hop met high fashion. It blended the edge of the streets with the gloss of Hollywood. Artists like Aaliyah, OutKast, and Mary J. Blige appeared not just as musicians but as style icons. For a time, it was the bridge between hip hop and mainstream culture, a perfect reflection of the ’90s when music videos were directed like short films, and rappers like Tupac became household names, both admired and feared.

Vibe’s editorial team, including Alan Light and Danyel Smith, focused on showcasing not just the music but the larger-than-life personas behind the mic. They highlighted the intersections of hip hop, R&B, and pop culture, presenting a multi-dimensional view of the genre. Vibe didn’t just report on what was happening; it forecasted the future.

Yet, as hip hop became more mainstream, the very edge Vibe celebrated began to dull out. While it persisted as an online entity, the print version bowed out in 2014, leaving a gaping hole in the culture’s storytelling.

R.I.P – Rap Pages (1989–2002): For the Underground

Rap Pages was the antithesis to the glossier hip hop publications. Founded by Lawrence “Larry” Flynt in 1989, this magazine catered to the underground, highlighting the voices and stories that mainstream media overlooked. This was the magazine that spoke directly to the purists—the ones who lived for the mixtapes, the freestyle battles, and the gritty, unpolished side of hip hop.

With editorial contributions from B+ (Brian Cross) and Soren Baker, the magazine was known for its investigative pieces and long-form interviews that peeled back the layers of the music industry. It wasn’t about the bling; it was about the bars. Rap Pages brought attention to West Coast artists like Dr. Dre and Ice Cube during a time when East Coast dominance was being questioned.

Rap Pages was a cultural critic, observing hip hop from the ground level. It refused to pander to trends and instead stood as a testament to the rawness of the genre. Yet, like many others, it couldn’t withstand the shift to digital consumption and closed shop in 2002, but its influence remains in the underground scene even today.

R.I.P – XXL (1997–2023): The Last Titan

Launched in 1997 by Harris Publications, XXL entered the game just as The Source was beginning to lose its way. XXL positioned itself as the magazine of the people, known for its no-holds-barred approach to journalism. With an editorial team led by Elliott Wilson, and later Vanessa Satten, XXL redefined what it meant to be a hip hop magazine in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

The XXL Freshman List became the ultimate co-sign for up-and-coming artists. XXL wasn’t just reporting on who was next—it was crowning them. Artists like Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, and Chance the Rapper were all early inductees, earning their stripes before mainstream success.

XXL kept its cultural pulse alive longer than most, continuing to print until 2023, but the internet eventually caught up. In an era where hip hop news was being disseminated in real time via blogs and social media, XXL’s print version was finally retired, leaving behind a digital legacy that still holds weight in hip hop circles today.

R.I.P – Hip Hop Connection (1988–2009): The UK’s Golden Child

Though American magazines dominated the conversation, the UK had its own hip hop bible—Hip Hop Connection. Founded in 1988 by Chris Hunt, this was the first monthly magazine dedicated solely to hip hop, preceding The Source by a few months.

With editorial contributions from the likes of Andy Cowan and later HHC stalwarts like Philip Mlynar, Hip Hop Connection provided a platform for both UK and US artists. It wasn’t just about the music; it was about culture, graffiti, breakdancing, and the elements that made hip hop a lifestyle rather than a genre.

It stayed true to its roots, refusing to bend to commercial pressures. However, with the rise of digital media, Hip Hop Connection couldn’t maintain its print circulation and ceased publication in 2009, taking with it a slice of UK hip hop history that can never be replaced.

Rest In Power – The Cultural Edge: Hip Hop Magazines Were More Than Paper

These magazines represented more than just glossy pictures and catchy headlines—they were the physical embodiment of a culture. Hip hop was not just something you listened to; it was something you wore, read about, argued over, and cherished like sacred scripture. For the fans, the artists of the time—Eric B, Rakim, KRS1, Tupac, Biggie, Nas, Jay-Z, Lauryn Hill—were more than musicians. They were poets, prophets, and philosophers.

The pages of these magazines bore the souls of artists that fans around the world knew they might never meet. But through the photoshoots, the interviews, and the essays, they came close. It was an experience deeper than words on a microphone; it was the documentation of a movement that spoke to the disenfranchised, the dreamers, the rebels.

The internet may have taken the torch from print, but those of us who still remember that walk to the bookshop, or receiving a copy via the Shatale Post Office in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga, that excitement of unwrapping a brand new issue, feel that something priceless was lost. Rest in power to the magazines that shaped our craft. Those were the days of soul-branding hip hop, where fashion labels told as much of the story as the music and the controversial lyrics did. Those were the days of intellectual lovemaking with paper and ink, and for a generation of die-hard fans, they remain irreplaceable. – Gazankulu.com

Add Comment